As the honorable Subhuti of good deeds and will, the venerable Mahakaccayana of great thought, the wise Mahakassapa, and the mighty Mahamoggallana heard this fresh wisdom, this revelation from the mouth of the Enlightened One, they were struck by wonder, awe, and profound joy. The future path of Sariputta toward superior enlightenment unfurled before them in divine revelation, enthralling their hearts and minds.

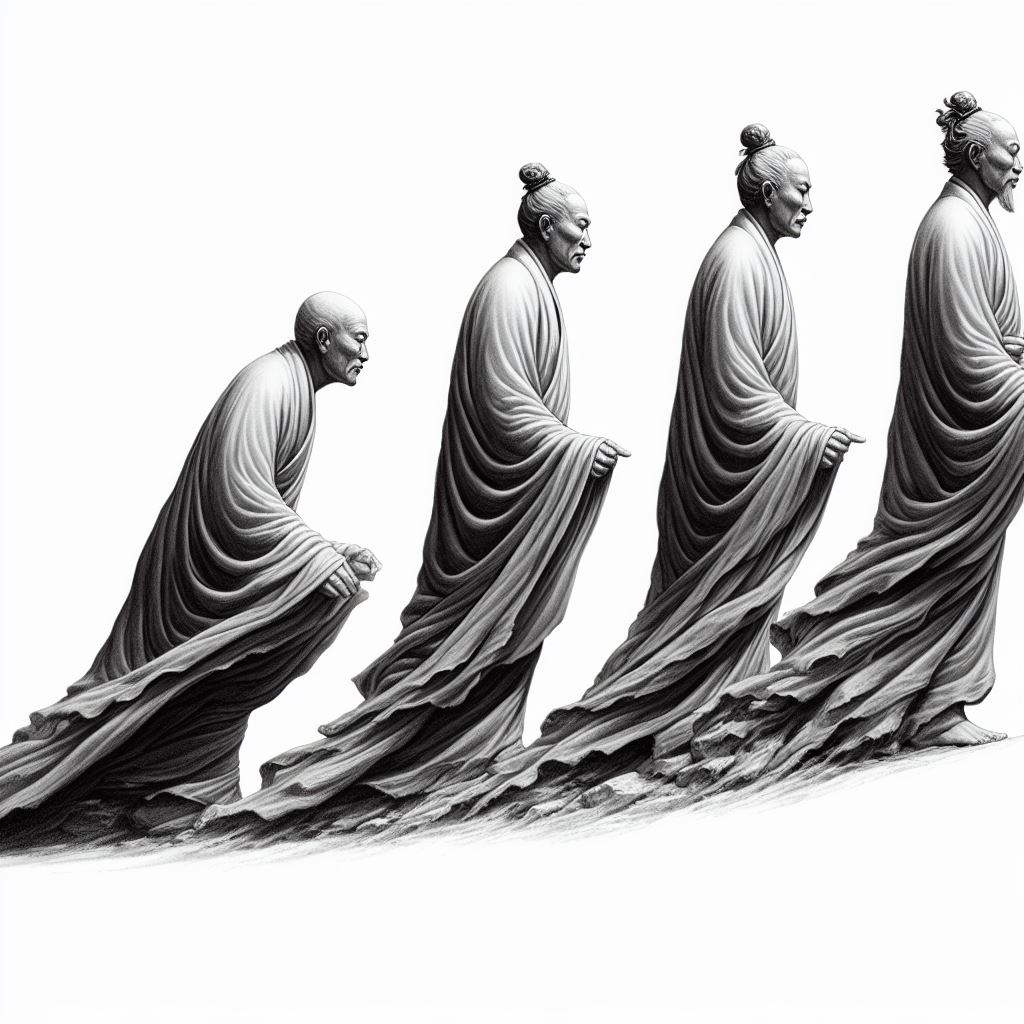

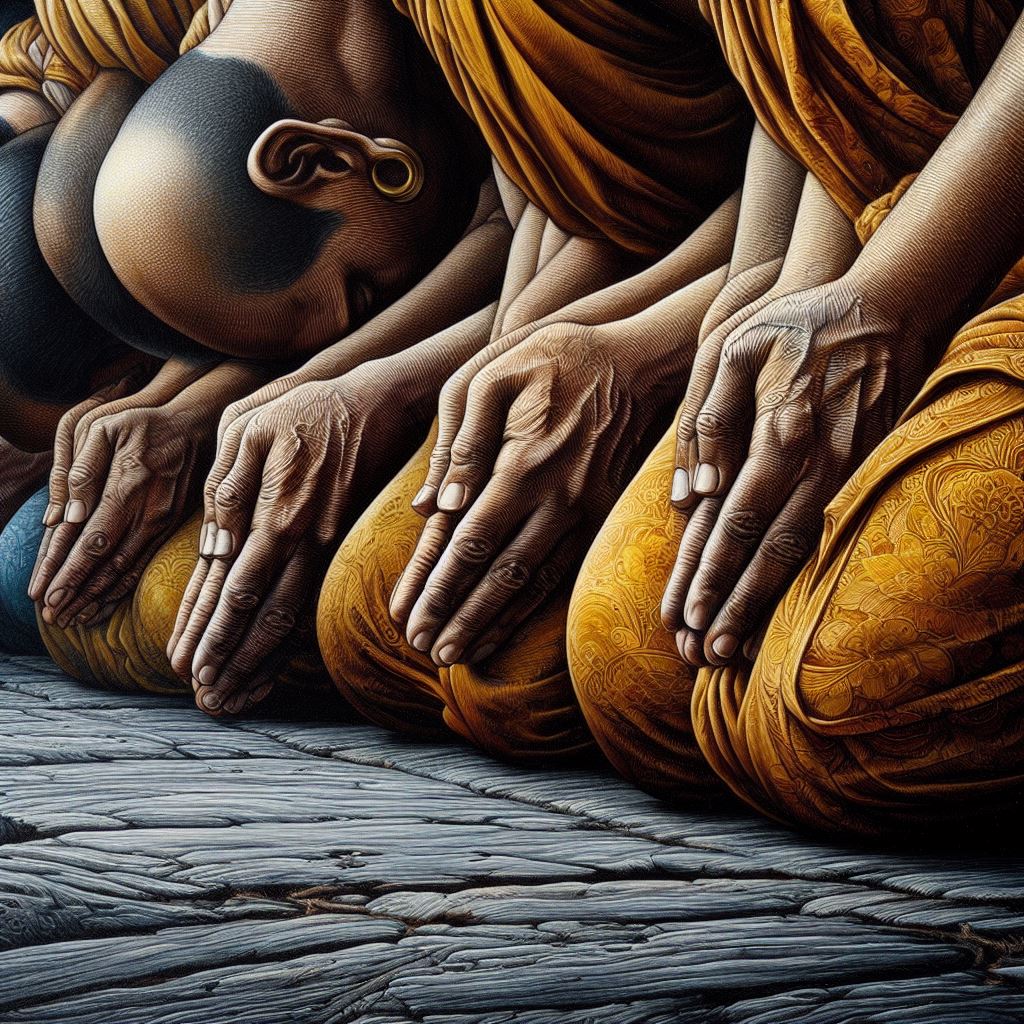

Suddenly, they rose from their seats as if guided by an unseen force. They moved towards where the Lord sat, casting their cloaks over one shoulder as tradition dictates. As they knelt on the hardened ground, right knee fixed in homage, they lifted their hands joined in reverence to the Enlightened One. Their bodies bent in humility, and their heads bowed with devotion, they prepared to address the Enlightened One, their voices carrying the weight of their awe and respect.

“Enlightened One,” they began, “we are of advanced age, revered as elders in this gathering of monks. Worn by time, we believed that we had found Nirvana; we no longer strive, O Lord, for the supreme perfect enlightenment; our strength and perseverance have waned. Despite your teachings, your long sitting, and our dedication to your sermon, our bodies betray us. Even as we have sat here in your holy presence, our limbs, joints, and very bones have begun to ache. In the face of your preaching, we struggle to comprehend that all is transient, without inherent purpose, without fixed essence. We yearn not for the Buddha’s laws, the manifold realms of enlightenment, or the miracles of the Bodhisattvas or Tathagatas. Escaping the confines of the triple world, O Lord, we thought we had reached Nirvana, yet we are but worn with age.

“Though we’ve inspired other Bodhisattvas, and guided them towards supreme perfect enlightenment, we’ve not once felt the stirring of desire. And now, O Lord, we hear from you that even disciples like us may be predestined for supreme perfect enlightenment. We are struck with wonder, with awe. What a blessing, O Lord, that we have heard such words from you today, unlike any we’ve heard before. We have found a precious jewel, O Lord, an unparalleled treasure. We had not sought nor even dared to dream of such an exquisite jewel. It is clear to us now, O Lord; it is clear to us, O Well Gone One.”

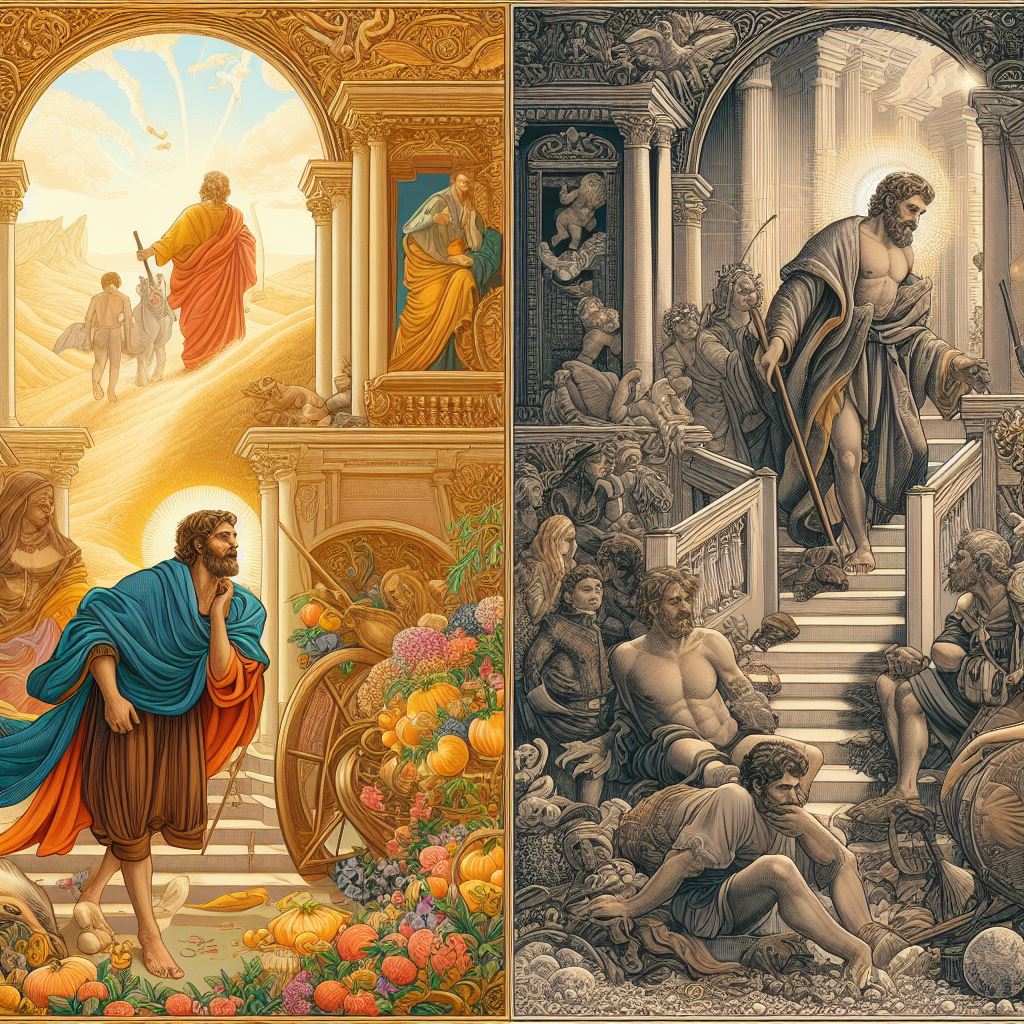

Imagine, O Lord, a confident man who leaves his father’s side and sets off for foreign lands. There, he lives for many decades—twenty, thirty, forty, and even fifty years. As time passes, the father becomes a man of great stature, while the son finds himself impoverished. Striving for a mere livelihood, desperate for food and clothing, the son roams far and wide, ending up in some distant place while his father moves to another land entirely.

The father amasses enormous wealth: he gathers gold and grain, treasures and storehouses; he acquires exquisite gold and silver, gems, pearls, sapphires, conch shells, and rubies, corals; he has a multitude of servants, both male and female, workers for menial tasks, and countless skilled laborers. He is rich in elephants, horses, chariots, cattle, and sheep. His retinue is vast, his investments span vast lands, and he conducts grand ventures in business, money-lending, farming, and trade.

In time, O Lord, the impoverished man, driven by his desperate search for food and clothing, traverses villages, towns, districts, provinces, kingdoms, and royal capitals, eventually arriving where his wealthy father resides. The father, blessed with abundant wealth and resources, dwells in this city. For all the fifty years since his son’s departure, he has held the image of his lost child in his heart, an ache that never left him. He spoke not a word of this longing to others, but yearned inwardly, thinking: ‘I am old, weathered by time, blessed with a wealth of gold, money, grain, treasures, and storehouses, yet I have no son. I fear death will come, and all this will be wasted, never to be used.’ Again and again, his thoughts turned to his son, ‘Oh, what joy it would bring me if only my son could enjoy this immense wealth!’

Meanwhile, O Lord, the poor man, in his relentless quest for food and clothing, was drawing nearer and nearer to the wealthy man’s mansion—his father, unbeknownst to him—the owner of the abundant treasures and resources. As fate would have it, the father was seated at the entrance of his grand abode, surrounded by a great throng of Brahmans, Kshatriyas, Vaisyas, and Sudras. There he sat on an opulent throne, its footstool adorned with gold and silver. He was managing vast sums of gold pieces, fanned with a chowrie, under a magnificent awning inlaid with pearls and flowers, embellished with hanging garlands of jewels. In short, he was seated amidst great pomp and spectacle.

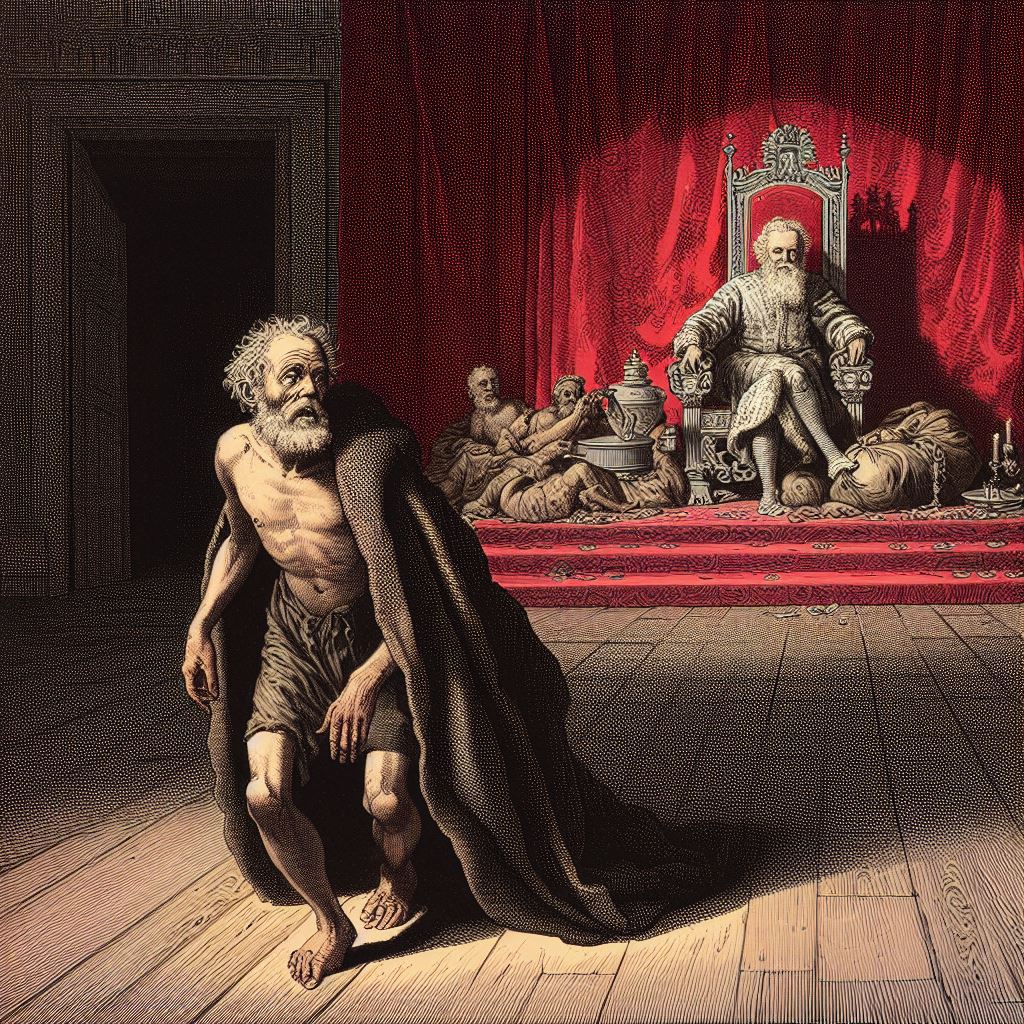

When the poor man saw his father in such grandeur at the doorway of the house amidst a great crowd of people conducting the affairs of a householder, he was struck by fear and trepidation. His heart raced, his body shivered, and his mind was a whirlwind of terror. He thought, ‘Have I encountered a king or a grand noble? This is no place for a man like me. I should go to where the poor reside; I could easily find food and clothing. I must leave this place immediately, lest I be forced into labor or face some other harm.’

Upon this realization, O Lord, the poor man swiftly retreats, fleeing in haste, lingering not a moment more, consumed by fear of the imagined dangers. Meanwhile, the wealthy man seated on his throne at the entrance of his mansion instantly recognizes his son. A surge of joy floods his heart, he is filled with delight and satisfaction, and his spirit soars with happiness. He thinks to himself, ‘Amazing! The one who will inherit this wealth of gold, money, grain, treasures, and storehouses, whom I’ve missed and thought of incessantly, is here now, in my twilight years.’

At that very moment, O Lord, the wealthy man dispatches his servants, commanding, “Go, gentlemen, and swiftly bring that man to me.” The servants race off, quickly overtaking the poor man. Seeing them approach, the poor man trembles with fear. His body shudders, his mind reels, he cries out of distress, screams, and pleads, “I’ve done you no harm!”

Despite his pleas, the servants seize the poor man and drag him. His fear intensifies, his body shudders even more, and his mind is chaotic. He thinks, ‘I fear they’ll put me to death; I am doomed.’ Overwhelmed with fear, he loses consciousness and collapses to the ground.

Seeing this, his father is filled with dread, teetering on the edge of despair. He commands his servants, “Do not handle the man in such a manner.” He sprinkles cold water on the unconscious man, refraining from saying more. The wealthy man, fully aware of his son’s humble situation and his own lofty position, recognizes the poor man as his son.

The wealthy man, O Lord, skillfully hides the truth from everyone—that the poor man is indeed his son. He summons one of his servants, instructing him, “Go, my good man, and tell the poor fellow, ‘You are free to go wherever you wish.’” The servant does as instructed, telling the poor man, “You are free to go wherever you wish.” Hearing these words, the poor man is taken aback. He leaves the place and heads back to the street of the impoverished in search of food and clothing.

To draw the man closer, the wealthy father employs a clever tactic. He seeks out two men of unremarkable appearance and humble stature. He tells them, “Go find the man you saw earlier and hire him in your name for double the daily wage. Ask him to work here in my household. And if he questions, ‘What work shall I be doing?’ Tell him, ‘You’ll help us clear a heap of dirt.’”

The two men locate and engage the poor man for the aforementioned work. Together, they clear the heap of dirt in the house, receiving daily pay from the rich man. They reside in a small straw hut near the wealthy man’s dwelling.

Through a window, the wealthy man observes his son clearing the heap of dirt. Seeing this, he is once again filled with wonder and astonishment.

Then the wealthy man leaves his mansion, removes his wreath and ornaments, and sets aside his elegant, pristine attire. He dresses in dirty clothing, takes a basket in his right hand, covers his body with dust, and approaches his son. He calls out from a distance, “Please, take these baskets and promptly clear the debris.” By doing so, he finds a way to speak to his son, to converse with him.

“Do stay here and work for me,” he says. “Don’t go elsewhere. I will pay extra. Feel free to ask me if you need anything—be it the cost of a pot, pool, boiler, firewood, salt, food, or clothing. Ask me if you need an old cloak, and I’ll provide it. If you require any tool, I’ll supply it. Be comfortable here, my friend. You can think of me as your father. I am older, and you are younger. You’ve provided me with many services by clearing this heap of dirt. Throughout your time here, I’ve seen no wickedness, arrogance, or dishonesty from you. I’ve seen none of the vices I’ve noticed in other servants. From now on, I regard you as my son.”

From that moment on, the wealthy man starts calling the poor man his son. The latter, in the company of the wealthy man, begins to regard himself as a son would to his father. Thus, longing for his son, the wealthy man keeps him occupied with clearing the pile of dirt for two decades. After all these years, the poor man feels completely comfortable entering and exiting the mansion, yet he still chooses to live in the humble straw hut.

As time passes, the rich man falls ill, sensing that his end is near. He calls the poor man and says, “Listen, my friend, I own a vast wealth – gold, money, grain, treasures, and storehouses filled to the brim. I am gravely ill, and I wish to pass on my riches to someone who would receive and take care of them. Please, accept it all. As I am the owner of this wealth, so now you are, but ensure that nothing of it is wasted.”

And so it came to pass, that the poor man accepted the rich man’s enormous wealth – the bullion, gold, money, grain, treasures, and storehouses. However, he remained unattached to this newfound fortune, taking nothing from it, not even the worth of a bag of flour for himself. He continued to live in his humble straw hut, feeling just as impoverished as before.

After some time, the wealthy man saw that his son had learned to manage, matured, and became mentally more robust. Now aware of his noble birthright, the son began to feel uncomfortable, ashamed, and repulsed by his previous life of poverty. As death drew near, the rich man summoned his son and gathered his relatives. Before the king or royal representative and in the presence of townsfolk and villagers, he declared, “Listen, everyone! This is my son, my flesh, and blood. It has been fifty years since he disappeared from a certain town. His name is such, and my name is such. In my search for him, I traveled from that town to here. He is indeed my son, and I am his father. I entrust all my wealth and income to him and recognize him as the rightful heir.”

And so, in disbelief, the poor man thought to himself, “Who would have thought? Out of nowhere, I’ve gained all this wealth, all this gold and grain, all these treasures and storehouses.”

In much the same way, Master, we see ourselves as children of the Enlightened One. And the Enlightened One tells us, “You are my children,” just as the wealthy man did. We were overwhelmed, Master, by three hardships: the hardship of suffering, the hardship of misconceptions, and the hardship of endless change. Lost in the whirlwind of worldly life, we were drawn to the lowly path. Then, Master, you inspired us to meditate on the countless minor laws, akin to a heap of dust. Once guided towards them, we worked hard, striving for nothing but Enlightenment, accepting it as our payment.

Contented, Master, with the Enlightenment we obtained, we thought we had received much from the Enlightened One because we had applied ourselves to these laws, and had put in effort. Yet, the Enlightened One paid us no heed, did not mingle with us, nor told us that this wealth of the Enlightened One’s knowledge would be ours. Even though, with skillful means, the Enlightened One appointed us as heirs to this wealth of wisdom. And we, Master, were not eagerly awaiting to claim this wealth because we already considered it a significant gain to receive Enlightenment as our pay from the Enlightened One.

We impart profound teachings about the wisdom of the Enlightened One to the Great Bodhisattvas. We explain, reveal, and validate the wisdom of the Enlightened One, Master, without any desire for personal gain. By his skill, the Enlightened One knows our disposition, while we do not know nor comprehend.

For this reason, Master, you now affirm that we are akin to your children and remind us that we are the heirs of the Enlightened One. Thus, we are like children to the Enlightened One, though humble in disposition. The Master sees the vigor of our spirits and bestows upon us the title of Bodhisattvas. But we are tasked with a dual role, as while we are termed humble beings in front of other Bodhisattvas, we are also called upon to stir them towards Enlightenment.

Recognizing the strength of our nature, the Master has thus spoken, and in this way, Master, we declare that we have unexpectedly and without longing attained the gem of all-knowing wisdom. We did not desire, sought, investigated, anticipated, or demanded this. Yet, we have received it, for we are indeed children of the Enlightened One.

Leave a comment