Modern life is a masterclass in distraction. Our days are filled with ambitions to chase, desires to satisfy, and an endless stream of entertainment to keep us occupied. We run from one goal to the next, building careers, seeking pleasure, and accumulating experiences, all while feeling productively engaged with the world. We are, by all accounts, playing joyfully.

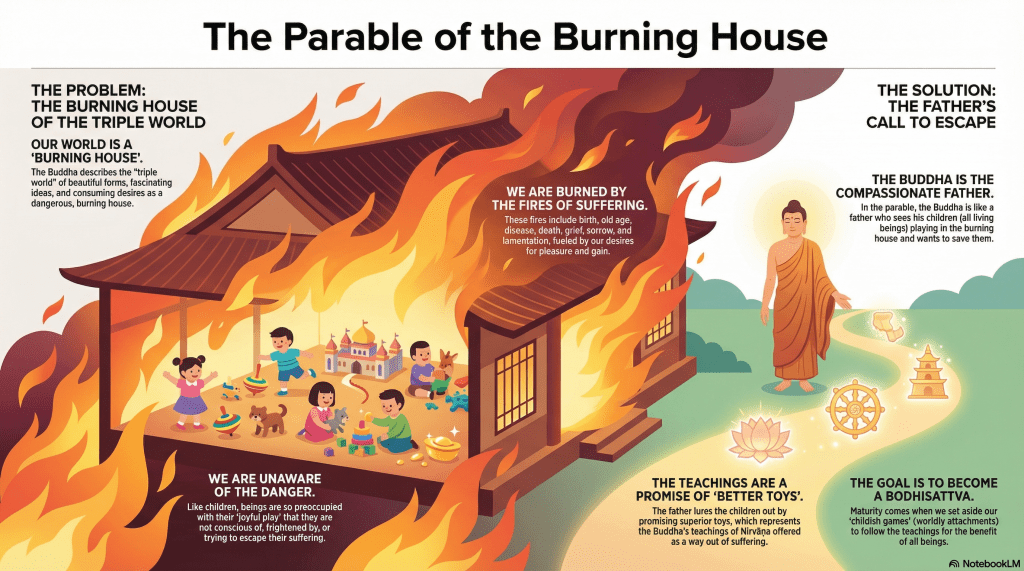

But an ancient parable from the Lotus Sūtra offers a startling and counter-intuitive perspective on our busy lives. It suggests that the world we find so engaging is not the playground we think it is. This powerful metaphor challenges us to look beyond our games and see the true nature of our situation. Let’s explore the key takeaways from this profound story.

Takeaway 1: The World You Know is a “Burning House”

The parable’s central metaphor is both simple and shocking: the “triple world”—the realm we experience through beautiful forms, fascinating ideas, and consuming desires—is not a playground but a “burning house.” The “fires” raging within it are the inherent and unavoidable sufferings of life: the pain of birth, the decay of old age, the affliction of disease, the finality of death, and the ongoing presence of grief, sorrow, and lamentation.

This idea is jarring because it directly confronts our most common perception of the world as a place for achievement and enjoyment. The parable asserts that while we are busy pursuing gain and satisfying our desires, we are simply “running about this burning house,” oblivious to the flames.

I see that all living beings are burned by the fires of birth, old age, disease, death, grief, sorrow, suffering and lamentation. They undergo various sufferings because they have the five desires and the desire for gain…Notwithstanding all this, however, they are playing joyfully.

Takeaway 2: Your Joyful “Games” Might Be a Dangerous Distraction

The parable continues by comparing humanity to children so preoccupied with their games that they cannot hear their father’s warning about the fire. Similarly, we become so engrossed in our own entertainment, ambitions, and desires that we fail to recognize the inherent suffering that surrounds and defines our existence.

This point is deeply impactful because it suggests that our most cherished pursuits and pleasures, far from being the ultimate goal of life, may actually function as a form of blissful ignorance. They are the “childish games” that keep our attention diverted, preventing us from seeing the deeper, more urgent truth of our situation. We are too busy playing to notice the smoke.

Takeaway 3: True Maturity Is Helping Others Escape the Fire

The parable’s resolution offers a path forward, but it’s one of profound empathy and skill. The father, seeing his children are too absorbed to heed a direct warning, doesn’t just shout “Fire!” Instead, he wisely lures them to safety “with a promise of better toys.”

This is the key to true wisdom, or our “maturity as Bodhisattvas.” It is not found by simply abandoning our games or scolding others for playing theirs. It comes from recognizing the danger and then developing the compassionate skill to meet people where they are. The path forward is not about judgment, but about skillfully offering a more compelling, more beautiful, and safer alternative to the dangerous distractions inside the house. It’s a profound shift in purpose: from self-centered play to a compassionate focus on the “benefit of all beings,” guiding them toward the exit with wisdom and care.

Conclusion: Waking Up from the Game

The parable of the burning house is a call to awaken. It asks us to look up from our distractions and see the world with clear, unvarnished perception. The core message is a challenge to evolve from an unconscious player absorbed in a game to a conscious actor who understands the larger situation and acts with wisdom and compassion. It’s about realizing that the point isn’t to win the game, but to get everyone out of the house safely.

What “games” in your life might be distracting you from the heat of the flames, and what would it mean to finally look up?

Leave a comment