Introduction: The Hidden Trap of Self-Improvement

It’s a natural human tendency. After months of discipline, we achieve a long-sought goal—a promotion at work, a new level of fitness, a consistent spiritual practice. In that moment of success, a subtle feeling can arise: a sense of superiority, a quiet judgment of those who haven’t achieved the same. We feel we have risen above, and in doing so, we look down.

This very human pitfall, the hidden trap of self-improvement, is addressed with profound clarity in an ancient Buddhist text, the Lotus Sūtra. This post will explore a single, powerful instruction given to a magnificent being, revealing a timeless truth about the nature of true progress.

The Bodhisattva’s Surprising Warning: Why Your Advantages Don’t Make You Better

The scene is set in Chapter Twenty-Four of the Lotus Sūtra. A highly advanced being, Wonderful-Voice Bodhisattva, resides in a world of perfection and wishes to visit our world—the “Sahā-World.”

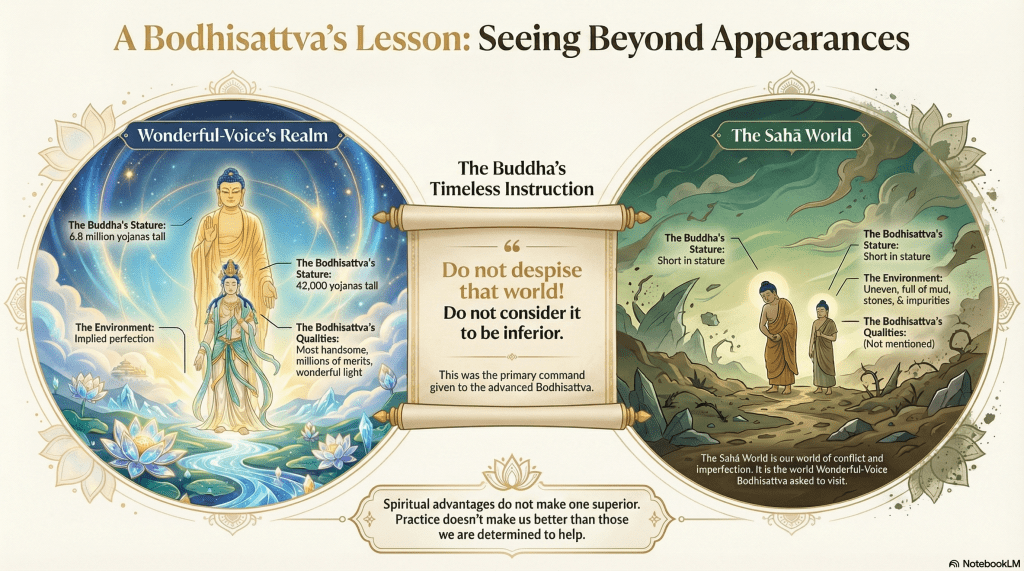

The contrast between these two realms could not be more extreme. The Bodhisattva is described as forty-two thousand yojanas tall, exceptionally handsome, and possessing “thousands of millions of marks of merits.” Our Sahā-World, by comparison, is “not even,” a place “full of mud, stones, mountains and impurities.” Its enlightened inhabitants, including its Buddha and Bodhisattvas, are seen as “short in stature.” Yet, before this magnificent Bodhisattva departs for our flawed world, his own Buddha, Pure-Flower-Star-King-Wisdom, gives him a critical and surprising warning.

He is told, with emphatic repetition:

“Do not despise that world! Do not consider it to be inferior [to our world]! Good Man! … Do not despise that world when you go there! Do not consider that the Buddha and Bodhisattvas of that world are inferior [to us]! Do not consider that that world is inferior [to ours]!”

This threefold instruction is so impactful because it is a direct antidote to the spiritual ego—the most subtle and dangerous form of pride, which feeds on accomplishment and turns progress into a tool for self-aggrandizement and separation. The warning is not just for a celestial being; it is for us. The Bodhisattva is an archetype for anyone on a path of self-improvement. His “thousands of millions of marks of merits” are the ultimate version of our smaller achievements. The moment we feel we have “arrived,” we are most at risk of falling into the trap of contempt.

The warning also reveals a profound paradox. Why would a being from a perfect world be sent to an imperfect one? The purpose of his journey is to benefit beings in this difficult realm. His advantages are not for him; they are tools for service. This insight reframes the entire concept of success—not as a personal status symbol, but as a resource for others. This instruction reveals a fundamental truth of the Dharma, a reminder that “no matter what advantages we have gained from our practice of the Buddha Dharma, these do not make us any better or worse than those we are determined to benefit.”

Conclusion: A Final Thought

True growth is not measured by how far we rise above others, but by our capacity to dissolve the very ideas of “above” and “below.” It is the recognition that our strengths find their highest purpose not in creating distance, but in closing it, using whatever light we have gained to illuminate the ground we all share.

In our moments of achievement, when we feel most accomplished, can we notice the subtle temptation to despise the “mud and stones”—and choose instead to see them as the very ground where our true work begins?

Leave a comment