Introduction: The Unasked Question

We live in an age of information overload, yet one of our deepest questions remains unanswered: Who are we, really? We feel adrift in a sea of our own thoughts, anxieties, and fleeting identities. We are constantly constructing and deconstructing ourselves, chasing a sense of a stable, authentic self, but often feeling more lost than when we began. This modern-day quest for identity, this feeling of being a stranger in your own head, can feel uniquely overwhelming.

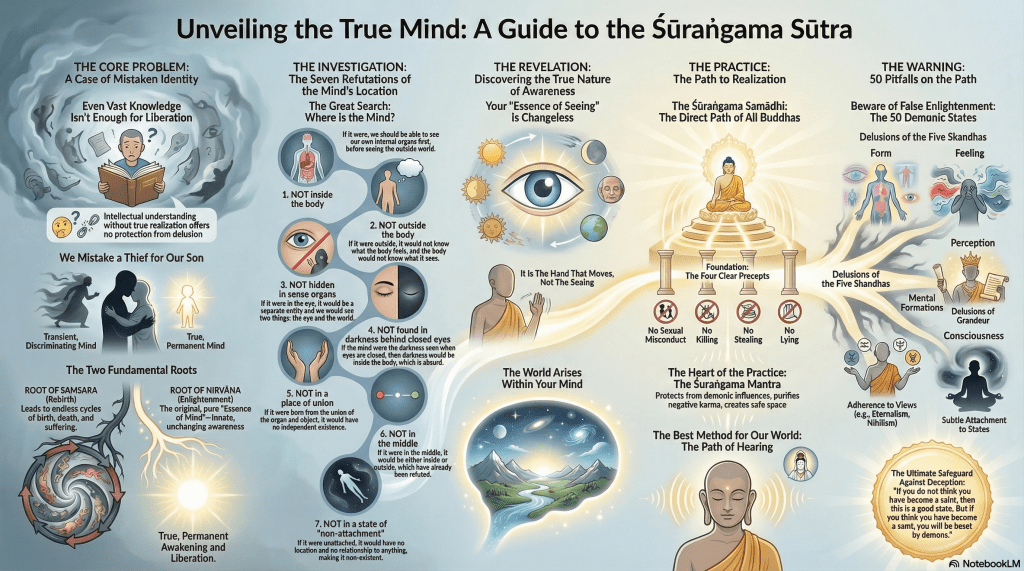

Yet, these are not new questions. Over a thousand years ago, an ancient Buddhist text called the Śūraṅgama Sūtra explored these exact existential puzzles with stunning clarity. Through a series of profound dialogues between the Buddha and his disciples, the Sūtra systematically dismantles our most common assumptions about who we are and where our mind is located. What follows are six of its most startling and counter-intuitive insights—paradoxes that challenge the very foundation of your perceived reality and remain profoundly relevant today.

——————————————————————————–

1. The Thief in Your Head: Your Thinking Mind Isn’t Your True Self

The Sūtra begins with a simple question: Where is your mind? The Buddha’s disciple, Ānanda, assumes it is inside his body. But the Buddha invites Ānanda—and us—to look closer. If your mind is truly inside your body, he asks, then it should perceive its immediate surroundings first. You should be aware of your own liver, heart, and spleen before you ever see the world outside. Is there anyone who first sees their own internal organs and only then observes the external world? The logic is immediate and unassailable.

Then he asks, what if the mind is outside the body? In that case, your mind and body would be disconnected. Your mind could know things your body couldn’t feel, and your body could feel things your mind wouldn’t know. Through a series of seven such refutations, the Buddha systematically proves that what we typically call our “mind”—the ceaseless inner chatter, the stream of thoughts and judgments—has no fixed location at all.

This leads to the Sūtra’s first radical conclusion: the discriminating, thinking mind we so thoroughly identify with is not our true self. It is a series of “false conceptions” that arise from our contact with the external world through our senses. For our entire lives, we have mistaken this imposter for our innermost being.

This idea is a profound challenge to your most basic assumption that the voice in your head is you. If your thoughts are not your true self, what is? This is where the true investigation begins. The Buddha uses a powerful metaphor to describe this fundamental error of identity.

“This is merely a false conception of phenomenal distinctions, which confuses your true nature. From beginningless time to the present, you have been ‘recognizing a thief as your son.’ You have thus lost your own eternal source and so incurred the transmigrations of birth and death.”

——————————————————————————–

2. The Part of You That Never Ages

As we grow older, the physical evidence of time’s passage becomes undeniable. In the Sūtra, King Prasenajit comes to the Buddha deeply distressed by this reality. He points to his wrinkled face and decaying form as proof of his inevitable destruction, a sign that he, as a being, is impermanent and doomed to vanish.

The Buddha’s response offers one of the most beautiful shifts in perspective on aging ever recorded. He asks the King to recall at what age he first saw the Ganges River. The King remembers seeing it as a small child of three. The Buddha then points out that while the King’s face has wrinkled and his body has decayed dramatically since he was a boy, the fundamental nature of his seeing has not wrinkled, aged, or changed at all.

This is a powerful pointer toward a deeper identity. It separates your true nature from your perishable physical form. While your body is subject to change and decay, the pure awareness that experiences the world through it is changeless. It is an essence within you that exists outside of birth, death, and the relentless march of time.

“Your Majesty, your face is wrinkled, but the essential nature of your seeing has not wrinkled. What wrinkles is subject to change. What does not wrinkle is changeless. What is changing must be extinguished. That which is changeless is fundamentally without birth or death.”

——————————————————————————–

3. The Universe in a Bubble: Reality Is a Projection of Mind

One of the most mind-bending teachings in the Sūtra is its view of reality. You typically assume you are a small, fragile being existing within a vast, external universe. The Sūtra flips this assumption on its head. It states that the entire physical world—”mountains, rivers, the void, and the great earth”—is not separate from you but actually exists within your true, wondrously bright Mind.

To explain this, the text offers a brilliant analogy. You are like a person who stands before the ocean but ignores its vastness, instead mistaking a single, tiny floating bubble for the entirety of the water. In this metaphor, your physical body and the world you perceive through it are the bubble. Your True Mind is the boundless ocean itself.

The implication is staggering: you are not a small consciousness contained within a body, which is in turn contained within a universe. Instead, your True Mind is the container for all of it. You are the vastness itself, experiencing reality from a localized, seemingly limited perspective.

“You do not know that your physical body, and the mountains, rivers, the void, and the great earth outside, are all objects within the wondrously bright, true Mind… It is as if one were to forsake hundreds of thousands of clear, pure seas, and recognize only a single floating bubble as the entire ocean.”

——————————————————————————–

4. Don’t Mistake the Finger for the Moon

Spiritual paths are often defined by their words, doctrines, and concepts. The Sūtra offers a timeless warning about the purpose of these teachings through one of its most famous analogies: the finger pointing at the moon.

The Buddha explains that his words and teachings are merely tools. They are like a finger pointing to the moon. The goal is not to study the finger but to use it as a guide to see the moon for yourself. The moon represents ultimate reality, a direct, unmediated experience of the truth. If a person becomes obsessed with the finger—analyzing its shape, length, and texture—they will have missed the entire point. In their intellectual fixation, they lose sight of not only the moon but also the finger, which has become useless.

This is a profound critique of dogmatism and the tendency to intellectualize spirituality. It emphasizes that direct experience is paramount. Words, concepts, and scriptures are only valuable insofar as they guide you toward that experience. Once they become objects of attachment in themselves, they become obstacles.

“It is like a person pointing a finger at the moon to show it to others. Those people should look at the moon by following the finger. If they look at the finger and mistake it for the moon, they not only lose sight of the moon, but they also lose the finger.”

——————————————————————————–

5. Are You the Guest or the Host? Discerning Your True Nature

If our thoughts are not our true self, how can we learn to distinguish between the transient chatter and our stable, underlying nature? The Sūtra provides two simple but elegant analogies for this practice.

The first is the metaphor of the guest and the host. Your fleeting thoughts, feelings, and sensory perceptions are like a “guest” who stops at an inn for a short time before moving on. Your true, unchanging nature is the “host” or innkeeper, who always remains. Our fundamental mistake is that we identify with the ever-changing guest instead of the ever-present host.

A similar analogy is that of dust and space. Your mental activity—the stream of thoughts and emotions—is like “dust” stirred up and moving in the wind. Your true nature is the vast, still “space” in which the dust moves. The dust is in constant motion, but the space itself is fundamentally empty, still, and undisturbed by what passes through it.

These analogies are not just poetry; they are the practical method for dealing with the “thief in your head” identified in the first paradox. By learning to see thoughts as “guests” or “dust,” we shift our identity to the ever-present “host” or “space”—the very true nature the Sūtra points toward.

“The one who does not stay is called the guest. The one who stays is called the host… What moves is called ‘dust’; what is still is called ‘space’.”

——————————————————————————–

6. The Madman Who Lost His Head

The Sūtra illustrates the nature of delusion with the strange and memorable story of a man named Yajñadatta. One morning, Yajñadatta looked in a mirror and became infatuated with his reflection, loving the way his eyebrows and eyes appeared so clearly in the glass. But then a dreadful thought arose. He grew angry at his own real head for its perceived failure to have a face and eyes he could see directly. In a flash of panic, concluding he must be a headless ghost, he ran screaming through the streets in a mad frenzy.

The resolution, of course, is that his madness was entirely baseless. His head was there all along. When he was finally made to realize this, he didn’t “gain” his head back from somewhere else; he simply ceased the groundless delusion. His panic had no real cause, and his “enlightenment” was not an achievement but a cessation of a pointless fear.

This story serves as a perfect metaphor for our own spiritual confusion. Our core delusion—the belief that we are separate, limited, and lacking our true nature—has no real foundation. It is a baseless panic born from attachment to an image and aversion to reality. Enlightenment, therefore, is not about gaining something you don’t have. It is about stopping the frantic search and realizing the true nature that was never, ever lost.

“Since it is called ‘delusion,’ how could it have a cause? If it had a cause, how could it be called delusion?… When his madness suddenly ceased, his head was not something he got from the outside. Even before his madness ceased, how could he ever have lost it?”

——————————————————————————–

Conclusion: What Was Never Lost

The insights from the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, though ancient, speak directly to our modern search for self. They weave a single, consistent theme: your true nature is not something you need to build, find, or achieve. It is not a distant goal to be reached after years of striving. Rather, it is the ever-present reality of your being, something you must simply uncover by seeing through your own baseless delusions.

The text invites you to stop identifying with the thief of your thoughts, the aging of your body, and the bubble of your perceived world. It asks you to look where the finger is pointing, to recognize yourself as the host and not the guest. If your deepest anxieties are as baseless as a madman’s fear of his own head, what would it mean to simply stop running?

Leave a comment