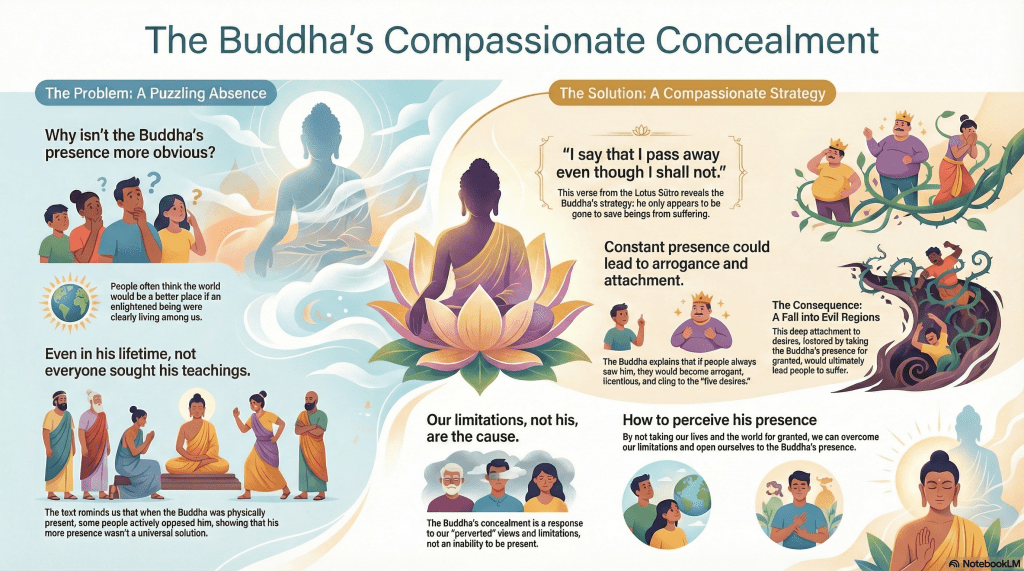

In moments of personal struggle or when faced with global suffering, it’s natural to ask: if enlightened wisdom exists, why does it feel so absent? We often think that if only we could see a living Buddha or a perfect guide, our own spiritual paths would become clearer, our suffering would lessen, and the world would surely be a better place.

This question feels modern, but it’s one that spiritual traditions have grappled with for millennia. The answer, at least according to one of Buddhism’s most revered texts, the Lotus Sūtra, is not what we might expect. It suggests that the Buddha’s apparent absence is not a void, but a profound and compassionate teaching in itself, a deliberate act designed for our ultimate benefit.

Why a Constant Guide Would Hinder, Not Help

The first part of this teaching is that if people could always and easily see the Buddha, they would ultimately take him and his teachings for granted. Instead of being inspired to do the difficult work of self-improvement, we would become “arrogant and licentious.” In a modern sense, this points to a kind of spiritual complacency or materialism, where having easy answers would prevent us from undertaking the real inner transformation. We would remain attached to “the five desires”—the endless pursuit of pleasure through our senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—rather than seeking a deeper, more lasting fulfillment.

In Chapter Sixteen of the Lotus Sūtra, the Buddha explains this directly:

I am saving all living beings from suffering.

Because they are perverted,

I say that I pass away even though I shall not.

If they always see me,

They will become arrogant and licentious,

And cling to the five desires

So much that they will fall into the evil regions.

This insight is powerful because it completely flips our conventional expectations. It suggests our spiritual longing is not for a savior to do the work for us, but for the necessary space to undertake the work ourselves. This paradoxical idea—that the Buddha’s constant presence would be a hindrance—leads directly to the sūtra’s second, more personal insight: the barrier to enlightenment isn’t external, but internal.

The Veil is of Our Own Making

The second part of the argument is that our inability to perceive the Buddha is a result of our own inner limitations and “perversions.” The problem isn’t a lack of presence, but a lack of our own clarity.

The text reminds us that even when the Buddha was physically alive, his mere presence was not a magical solution for everyone. Not all people sought out his teachings, and some were even actively hostile toward him. This historical fact reinforces the idea that an external presence, no matter how enlightened, cannot force a change in those who are not ready to see it. The challenge, then, isn’t about finding the Buddha in the world, but about overcoming the internal obstacles that prevent us from recognizing the wisdom that is already here.

Ultimately, the Buddha’s seeming absence is presented as a profound form of skillful means. It is a compassionate strategy that protects us from the complacency that a constant presence would breed, forcing us instead to confront the internal obstacles that truly veil our perception. The silence we perceive is not emptiness. It is a sacred space carved out for us—an invitation to stop looking outward for a savior and to begin the courageous work of discovering that same luminous presence within ourselves.

What might change if we viewed this apparent absence not as a void, but as an invitation to discover that presence within ourselves?

Leave a comment