——————————————————————————–

1.0 Introduction: A Pan-Buddhist Architectonic Principle

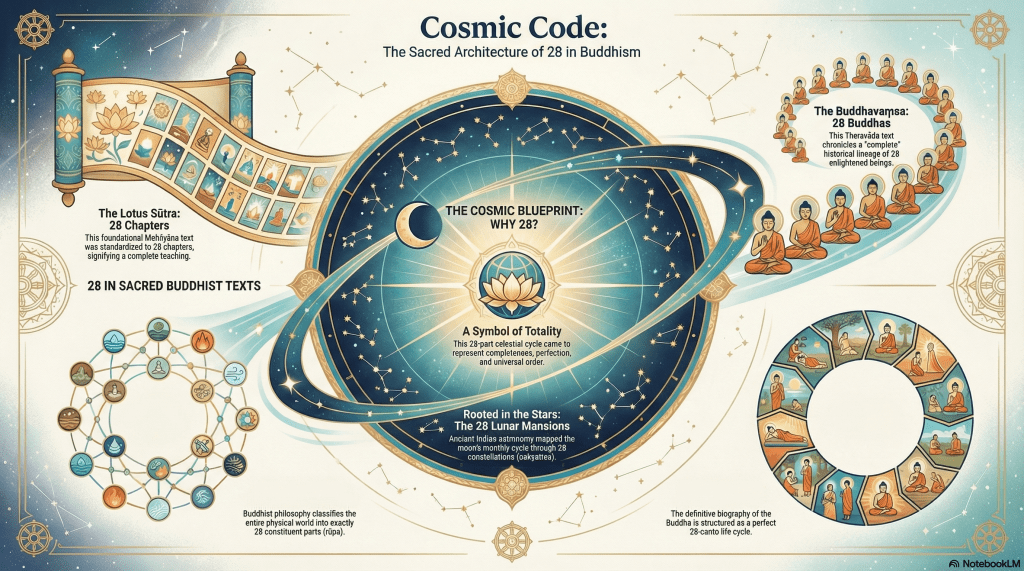

The study of numerological patterns in religious literature provides a critical lens for understanding how ancient traditions encoded meaning, organized knowledge, and asserted authority. In textual lineages with deep roots in oral transmission, such as Buddhism, structural features often serve simultaneous mnemonic, liturgical, and cosmological functions. In a recent contribution to the study of Buddhist numerology, William Altig posits a compelling thesis that warrants careful consideration: that the number twenty-eight functions not as a series of isolated coincidences but as a deliberate and pervasive “architectonic principle” symbolizing cosmological totality. This principle, he argues, forms a structural bridge connecting the seemingly disparate worlds of Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Altig builds his case upon a consistent pattern observed across a diverse range of canonical and para-canonical texts. The core examples that form the foundation of his argument include:

- The Lotus Sūtra, which in its definitive Chinese translation by Kumārajīva comprises twenty-eight chapters.

- The Buddhavaṃsa, which chronicles the complete lineage of twenty-eight past Buddhas.

- Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita, an epic biography of the Buddha structured in twenty-eight cantos.

- The Theravāda Abhidhamma’s exhaustive classification of all material qualities into twenty-eight fundamental rūpas.

The centerpiece of Altig’s contribution is his novel “Ideal Canon Hypothesis,” a speculative yet rigorously argued proposal concerning the textual history of the Pāli Dhammapada. He proposes that this foundational text, which currently exists in a twenty-six-chapter format, may be a contracted version of an original twenty-eight-chapter recension. The entire argument is anchored in a shared cultural and scientific framework that provides the symbolic weight for this sacred number.

2.0 The Astronomical Foundation: The Twenty-Eight Nakṣatras

To ground the numerological argument in a concrete, external system, Altig anchors the symbolic significance of twenty-eight in the ancient Indian astronomical system of lunar mansions, or nakṣatras. This framework provided a celestial map against which cosmological and religious ideas could be charted.

The twenty-eight nakṣatras represent the distinct constellations or asterisms that the moon appears to pass through during its sidereal month. The inclusion of an intercalary mansion (Abhijit) was crucial for completing the symbolic cycle, bringing the total to a perfect and closed set of twenty-eight. This number came to represent a complete circuit, a finished journey through the heavens.

Altig details a key historical shift in Indian astronomy where the system was mathematically rationalized from twenty-eight mansions to twenty-seven. This change was driven by the need for cleaner calculations, as the 360 degrees of the ecliptic are perfectly divisible by 27 (yielding 13°20′ per mansion) but not by 28. Crucially, Altig notes that the adoption of 27 mansions also enabled subdivision into four padas (quarters), yielding 108 total padas—a number that became sacred in both Buddhist and Hindu numerology. Despite this mathematical shift, the archaic count of twenty-eight was retained in liturgical and cosmological contexts precisely for its accumulated symbolic value.

The antiquity and cross-cultural reach of this framework are underscored by archaeological evidence, most notably the lacquered box from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng in China (c. 433 BCE), which is inscribed with the names of the twenty-eight mansions. This discovery demonstrates that the system was not confined to India but was a shared piece of pan-Asian scientific and cultural heritage. Altig argues that early Buddhist redactors deliberately adopted this well-established astronomical system to imbue their sacred texts with cosmic authority. By structuring scriptures and doctrines around the number twenty-eight, they positioned the Dharma not as a historically contingent teaching but as a universal, natural law that mirrors the timeless precision of celestial mechanics. From this cosmic origin, the number was applied directly to the architecture of foundational Buddhist texts.

3.0 Manifestations of ‘Totality’ in Canonical Texts

Having established the cosmological source of the number’s significance, Altig’s argument proceeds by demonstrating its consistent application across a diverse range of authoritative Buddhist texts. This pattern appears in works spanning hagiography, Mahāyāna scripture, and scholastic philosophy, suggesting a conscious and widespread editorial principle.

3.1 The Lineage of Buddhas: The Buddhavaṃsa

In the Buddhavaṃsa (“Lineage of Buddhas”), a Pāli canonical text, the chronicle of twenty-eight Sammā Sambuddhas (Perfectly Enlightened Ones) serves a crucial structural function. Altig analyzes this enumeration not as an arbitrary count but as the establishment of a “complete” and finite historical lineage of enlightenment. Just as the twenty-eight lunar mansions map a full celestial cycle, the twenty-eight Buddhas delineate the full scope of known salvific history, from the first Buddha, Taṇhaṅkara, to the historical Buddha, Gotama. This principle is extended into ritual practice through the Atthavīsati Paritta, or “Protective Chant of Twenty-Eight Buddhas,” which invokes the power of this complete lineage for safeguarding devotees.

3.2 The Cosmic Scripture: The Lotus Sūtra

The twenty-eight-chapter structure of the Lotus Sūtra is one of the most prominent examples of this sacred architecture. Altig evaluates the significance of Kumārajīva’s definitive 406 CE Chinese translation, emphasizing his decision to standardize the text at twenty-eight chapters. This stands in contrast to Dharmarakṣa’s earlier version, which contained only twenty-seven. Kumārajīva’s choice, Altig contends, reflects the “cosmological gravity” of the number, which helped establish the sūtra’s authority as a perfect and complete teaching.

This structure was given its most influential interpretation by the Tiantai patriarch Zhiyi, who divided the sūtra into two symmetrical halves, the jimen/shakumon and benmen/honmon:

- The Trace Teaching (Chapters 1–14): This first half focuses on the historical Śākyamuni Buddha, presenting his various teachings as “skillful means” to guide beings toward a single, unified path to enlightenment.

- The Fundamental Teaching (Chapters 15–28): This second half reveals the true nature of the Eternal Buddha, who attained enlightenment in the infinite past and whose historical appearance is merely a manifestation, or “trace.”

Zhiyi captured this relationship in a powerful metaphor: the fundamental teaching is the moon in the sky; the trace teaching is the moon reflected in a lake. This sacred structure found visual expression in Japanese art, particularly in the Kinji hōtō mandara (Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas). In these intricate works, the entire text of the sūtra’s twenty-eight chapters is transcribed in golden characters to physically form the body of a cosmic Buddha within a pagoda, making the textual architecture inseparable from the divine form.

3.3 The Perfected Life: The Buddhacarita

Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita, a 2nd-century CE Sanskrit epic, aligns the Buddha’s biography with the same numerological template. By structuring the narrative into twenty-eight cantos, the poem frames the Buddha’s life as a complete and perfect cycle, mirroring the astronomical progression through the nakṣatras. Altig notes that while the original Sanskrit is incomplete, the full twenty-eight-canto version survives in Chinese and Tibetan translations, confirming the work’s intended structure. He points specifically to the final, twenty-eighth canto, “The Division of the Relics,” as the narrative’s capstone. This concluding section describes the dispersion of the Buddha’s physical essence across the world, providing a textual parallel to the moon completing its journey through the final celestial mansion.

3.4 The Taxonomy of Reality: The Abhidhamma

The principle extends from narrative and scripture into the scholastic domain of the Theravāda Abhidhamma. Here, all of physical reality (rūpa) is systematically deconstructed into exactly twenty-eight constituent types. This exhaustive taxonomy provides a comprehensive map of the material world.

| Category | Count | Examples |

| Great Elements (mahābhūta) | 4 | Earth, water, fire, wind |

| Sensitive Organs (pasāda) | 5 | Eye, ear, nose, tongue, body |

| Objective Fields (gocara) | 4 | Visible form, sound, smell, taste |

| Sexual Qualities | 2 | Femininity, masculinity |

| Heart Base | 1 | Physical seat of mind |

| Life Faculty | 1 | Vitality |

| Nutrition | 1 | Nutritive essence |

| Space Element | 1 | Delimiting boundaries |

| Communication | 2 | Bodily and vocal intimation |

| Mutability | 3 | Lightness, softness, adaptability |

| Characteristics | 4 | Production, continuity, decay, impermanence |

| Total | 28 |

According to Altig, the soteriological purpose of this twenty-eight-fold classification is clear: it provides meditators with a complete analytical framework for deconstructing the conventional sense of self. By seeing reality as a flux of these twenty-eight impersonal phenomena, practitioners can directly realize the core truths of impermanence and not-self. The choice of precisely twenty-eight categories suggests a deliberate effort to create a system of “totality” that aligns the philosophical map of reality with the overarching cosmic structure. Having demonstrated the pattern in these established cases, Altig turns to his central, more speculative hypothesis concerning the Dhammapada.

4.0 The ‘Ideal Canon’ Hypothesis: A Case Study of the Dhammapada

The centerpiece of Altig’s contribution is his novel “Ideal Canon Hypothesis,” a speculative yet rigorously argued proposal concerning the textual history of the Pāli Dhammapada. He extends the “sacred architecture” thesis from known examples to argue that this foundational text, in its current twenty-six-chapter form, may be a contracted version of an original, ideal text that once comprised twenty-eight chapters.

4.1 The Textual Problem and Comparative Evidence

The extant Pāli Dhammapada is organized into twenty-six chapters containing 423 verses. Altig builds his case on textual anomalies within the Pāli version and on comparative evidence from other recensions, most notably the Gāndhārī Dharmapada. Citing John Brough’s seminal 1962 analysis, he highlights several key findings:

- The “Core 26” Hypothesis: Brough’s work suggests that the Gāndhārī, Pāli, and Sanskrit Udānavarga texts share a common ancestor structure centered on twenty-six chapters.

- Structural Fluidity: The Gāndhārī text demonstrates that chapter order was not fixed. Its first three chapters (Brāhmaṇa, Bhikṣu, Tṛṣṇā) appear in reverse order as the final three chapters of the Pāli recension, indicating significant editorial rearrangement across traditions.

- Intentional Design: The Gāndhārī manuscript exhibits clear structural planning, such as sequencing chapters by decreasing length and a physical gap at the manuscript’s midpoint, confirming that scribes were conscious of textual architecture.

The central anomaly that prompts Altig’s hypothesis lies in the final chapter of the Pāli recension, the Brāhmaṇavagga (“Chapter on the Brahmin”). At forty-one verses, it is nearly double the average chapter length, suggesting that it may not be a single, cohesive unit.

4.2 The Twenty-Eight-Chapter Hypothesis

Altig argues that the unusual length of the Brāhmaṇavagga is evidence of a textual merger. His thematic analysis reveals clear seams where distinct topics may have been combined into a single chapter.

| Verses | Theme | Potential Original Chapter |

| 383–386 | Liberation/The Unconditioned | → Nibbānavagga? |

| 387–409 | True Brahmin qualities | Brāhmaṇavagga (core) |

| 410–423 | Transcendence/Final Attainment | → Nibbānavagga? |

This structural evidence is compounded by a striking thematic omission in the Pāli text, which Altig frames with a powerful rhetorical observation: “Samsara has a chapter. Nirvana does not.” Despite Nirvāṇa being the central soteriological goal of the Buddhist path, the Pāli Dhammapada lacks a dedicated chapter on the topic (Nibbānavagga). This absence is conspicuous when contrasted with the Sanskrit Udānavarga, which preserves a distinct Nirvāṇavarga.

This leads directly to Altig’s hypothesis: if the verses on liberation were separated from the Brāhmaṇavagga to form a distinct Nibbānavagga, and if the text were expanded with another logical chapter such as a Tathāgatavagga (as seen in other recensions), the result would be a twenty-eight-chapter structure. This would align the Dhammapada perfectly with the pan-Buddhist numerological pattern observed in the Lotus Sūtra and other key texts. As corroborating evidence, Altig notes that the Mahāsaddanīti, a monumental Pāli grammar, also consists of exactly twenty-eight chapters, reinforcing the idea that this number was considered canonical for complete and authoritative works.

4.3 Scholarly Rigor: Alternative Explanations and Defeat Conditions

Demonstrating scholarly balance, Altig explicitly outlines the conditions under which his hypothesis could be weakened and acknowledges alternative explanations for the textual evidence.

4.3.1 Alternative Explanations

- Coincidence hypothesis: The number twenty-eight could simply be a culturally significant “round number,” with its appearance not always being the result of intentional design.

- Pattern-matching bias: A scholar may be prone to seeing patterns where none exist, driven by a pre-existing thesis.

- Practical transmission: Editorial decisions, such as the merging of chapters, may have been driven by practical constraints like manuscript length or material limitations rather than cosmological intent.

4.3.2 Defeat Conditions

Altig proposes specific, falsifiable conditions that would weaken his claim, such as the discovery of Gāndhārī recensions that explicitly preserve a 26-chapter format with no evidence of merger, or philological evidence that the key Nirvāṇa-related verses in Chapter 26 were composed much later than the chapter’s core material. This epistemic rigor frames his proposal as a well-reasoned hypothesis rather than a dogmatic assertion.

5.0 Synthesis: The Functions of a Sacred Architecture

Altig concludes his analysis by synthesizing the various examples into a unified theory of purpose. He argues that the number twenty-eight is not merely decorative but serves three distinct yet interrelated functions within Buddhist traditions, transforming it from a simple count into a powerful symbolic tool.

- Cosmological Anchor By linking textual structures or doctrinal lists to the twenty-eight lunar mansions, the tradition grounds the Dharma in the natural laws of the universe. This move elevates the teachings beyond human invention, presenting them as a cosmic truth that follows a predictable and perfect pattern. As Altig puts it, this serves to “remove ‘editorial accident’ and replace it with cosmic destiny.”

- Taxonomy of Totality The number is consistently used to create exhaustive and complete systems that provide a sense of intellectual and spiritual closure. The twenty-eight Buddhas of the Buddhavaṃsa represent the entirety of known spiritual history, while the twenty-eight rūpas of the Abhidhamma represent the entirety of the material world. To master these twenty-eight-fold lists is to gain a comprehensive knowledge of a particular domain, whether it is the lineage of saviors or the constituent parts of suffering.

- Liturgical and Mnemonic Scaffolding On a practical level, a twenty-eight-part structure offers a clear and robust framework for religious life. It facilitates the systematic study of long texts like the Lotus Sūtra, provides a structure for ritual chanting, and offers a tangible map for meditative practices, such as the deconstruction of the physical body in Abhidhamma-based contemplation.

6.0 Conclusion

This review of William Altig’s scholarship highlights a compelling and coherent argument for the intentional use of the number twenty-eight as a symbol of symbolic totality in Buddhist canonical literature. His core thesis posits that this number is not an incidental feature but a deliberate architectural choice used to signal a complete, perfect, and authoritative cycle across a wide spectrum of texts and traditions. By mapping the lineage of enlightenment, the structure of key scriptures, and the very constituents of matter onto this number, Buddhist redactors aligned the Dharma with the immutable order of the cosmos.

The “Ideal Canon Hypothesis” for the Dhammapada is particularly significant. If further textual evidence confirms that the Pāli version is a contraction of an original twenty-eight-chapter text, this would not only revise our understanding of the Dhammapada‘s editorial history but would also establish a numerological connection between Theravāda and Mahāyāna canonical traditions. It would demonstrate that the textual body and the cosmic body were conceived as one and the same, providing practitioners with a structured path to liberation inscribed in the very architecture of the scriptures they study. The moon completes its cycle in twenty-eight stations; so too, Altig suggests, does the Dharma.

Leave a comment