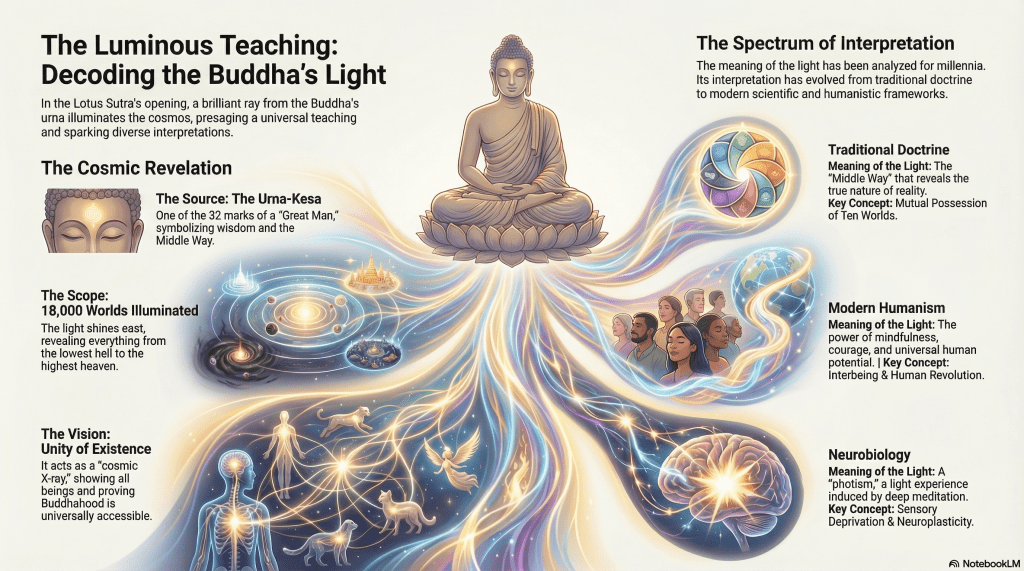

When we picture the Buddha, a common image comes to mind: a serene figure with a radiant halo or a glowing dot between his eyebrows. But on ancient Vulture Peak, this was no simple sign of divinity. The audience for this light wasn’t just human; it was a cosmic convergence of monks, kings, and a vast host of heavenly beings—devas, nagas, and even fiery asuras. What if this mystical beam was something far more profound than a special effect, a symbol encoding the deepest truths of reality for every being in attendance?

The ancient Lotus Sutra, one of the most revered texts in Mahayana Buddhism, opens with the Buddha emitting a brilliant ray of light from his forehead. This isn’t just a dramatic flourish; it’s a cosmic event packed with meaning. Here are five surprising truths about this light that reveal its true power, connecting the cosmic to the personal and the ancient to the cutting-edge.

——————————————————————————–

1. The Light Isn’t a Flashlight—It’s a Cosmic X-Ray

In the Lotus Sutra, the light’s primary job isn’t just to illuminate; it’s to reveal. The beam shines from the highest point of existence, the Akanishtha Heaven, all the way down to the lowest realm of suffering, the Avici Hell. In its glow, the entire cosmic assembly can suddenly see the karmic conditions of every being in every world. The vision is startlingly specific: they see monks practicing in forests, bodhisattvas perfecting their virtues, laypeople making offerings, and beings suffering the consequences of their actions in hell.

The implication is radical. It visually collapses the separation between different states of being, showing that a soul in torment and a saint in meditation are part of a single, unified reality. The light functions as a cosmic x-ray, making the hidden interconnectedness of all life visible.

This is a powerful demonstration that no being, no matter how lost in suffering, is outside the reach of awakening. The 13th-century Japanese master Nichiren saw this as definitive proof of universal potential.

“…this proves that ‘the seed of Buddhahood’ exists even in the most depraved beings.”

——————————————————————————–

2. It’s Not a ‘Third Eye,’ It’s a Wisdom Transmitter

The light originates from a very specific place: the urna-kesa, a white tuft of hair curled between the Buddha’s eyebrows. While often misinterpreted as a mystical “third eye,” the source texts describe it more like a dynamic transmitting device. The word urna itself is rich with association, linguistically linked to “wool,” “vessel,” and “receptacle,” suggesting it is both a container of profound wisdom and a projector of it.

Symbolically, its location between the two physical eyes represents the “middle way,” a perspective that transcends dualistic vision. The light it projects is a form of “Buddha-gnosis,” or direct wisdom. Far from being a simple white beam, this light can shift its color and intensity to meet the needs of its audience, acting as a series of targeted “karmic lasers.” It radiates as a great white light to purify ignorance, then shifts to purple, blue, and golden hues to dissolve specific karmic defilements.

The takeaway is profound: the light isn’t about the Buddha seeing visions with a third eye, but about transmitting a wisdom so powerful that it fundamentally changes how others see reality.

——————————————————————————–

3. The Light Might Just Be the Power of Mindfulness

For modern practitioners, this ancient story of cosmic light has been reinterpreted as a deeply personal psychological power. This humanistic approach is part of a long line of inquiry into the light’s meaning. The Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, for instance, taught that this brilliant beam is a poetic metaphor for the power of mindfulness (smrti).

He argued that when our attention becomes concentrated, it reveals the true nature of reality: Interbeing. This modern idea has ancient roots in cosmological metaphors like Indra’s Net, where every jewel in a vast web reflects every other jewel, creating a holographic universe. For Nhat Hanh, the light of mindfulness allows us to see this interconnectedness. To explain this, he used the beautiful metaphor of waves and water. Our lives are the “Historical Dimension,” the rising and falling waves of birth and death. The light of mindful presence allows us to “touch the water while riding the wave,” realizing our connection to the “Ultimate Dimension” which, like the water, is unborn and undying.

“When the light of mindfulness… illuminates a leaf, we see the whole universe in it.”

This interpretation makes a cosmic event deeply accessible. The power to illuminate all worlds isn’t reserved for a Buddha; it’s available to anyone through the practice of being present.

——————————————————————————–

4. Neuroscience Has a Surprising Explanation for Visions of Light

The continuous line of inquiry into the Buddha’s light now includes a fascinating dialogue with modern brain science. Researchers studying deep meditation have cataloged “meditation-induced light experiences” (photisms), which sound remarkably similar to the descriptions in ancient texts.

A proposed neurobiological mechanism for this is a process called deafferentation. In lay terms, this is where the visual cortex, starved of external input during prolonged meditation, becomes hyperexcitable and begins to generate its own signals, which are perceived as flashes or fields of light.

This aligns perfectly with the Lotus Sutra. Right before the light appears, the text states that the Buddha enters a profound state of meditative absorption called Anantanirdesa-pratisthana—the Samadhi of the Place of Immeasurable Meanings. The very conditions described in the sutra are those that neuroscience suggests can produce such phenomena. This scientific parallel doesn’t debunk the spiritual meaning but offers a compelling bridge between ancient contemplative insight and the workings of the human brain.

——————————————————————————–

5. It Inspired Spiritual Jazz and the “Lotus Sutra Blues”

Perhaps the most surprising truth is how this ancient image has been reinterpreted in modern Western music. Musicians and poets have drawn a powerful parallel between the Buddhist concept of suffering (dukkha) and the musical tradition of “the Blues,” which gives voice to hardship. In this context, the Buddha’s light is the luminous answer to the blues. Jazz saxophonist John Coltrane’s “sheets of sound”—overwhelming cascades of notes—were seen by many as a musical analogue for the light’s power to shatter mundane perception.

But the synthesis goes even deeper. In visionary works like the “Lotus Sutra Blues,” the light isn’t just a distant, heavenly beacon. In a radical reimagining that merges the teaching with African spirituality, the light is sometimes described as “black” or “blue,” representing the fertile void from which all things arise. This reclaims the light not as a pristine white beam, but as a soulful, earthy luminescence that rises from the “mud” of everyday suffering. It’s a testament to the symbol’s universal power to cross centuries and express the hope of transcendence in a completely new artistic language.

——————————————————————————–

The Buddha’s light is far more than a simple halo. It is a multifaceted symbol that serves as a cosmic x-ray, a wisdom transmitter, a metaphor for mindfulness, a subject of neuroscientific inquiry, and a source of artistic inspiration. It connects the cosmic to the personal, the ancient to the modern, and the spiritual to the scientific.

Ultimately, the light in the sutra is not just something to be seen, but something to become. It poses a question to us all: How might we emit our own light of wisdom and compassion to illuminate the worlds of our own communities?

Leave a comment