This briefing document examines the allegorical interpretation of “wonders” in Chapter Twenty-Seven of the Lotus Sūtra, “The Former Deeds of King Wondrous Splendor,” and how these ancient narratives translate into meaningful modern Buddhist practice. It highlights the transformation of supernatural feats into metaphors for internal and social change, emphasizing compassion, self-control, resilience, and respect as the true “wonders” of the bodhisattva path.

I. Introduction: Reinterpreting Supernatural Feats as Spiritual Transformation

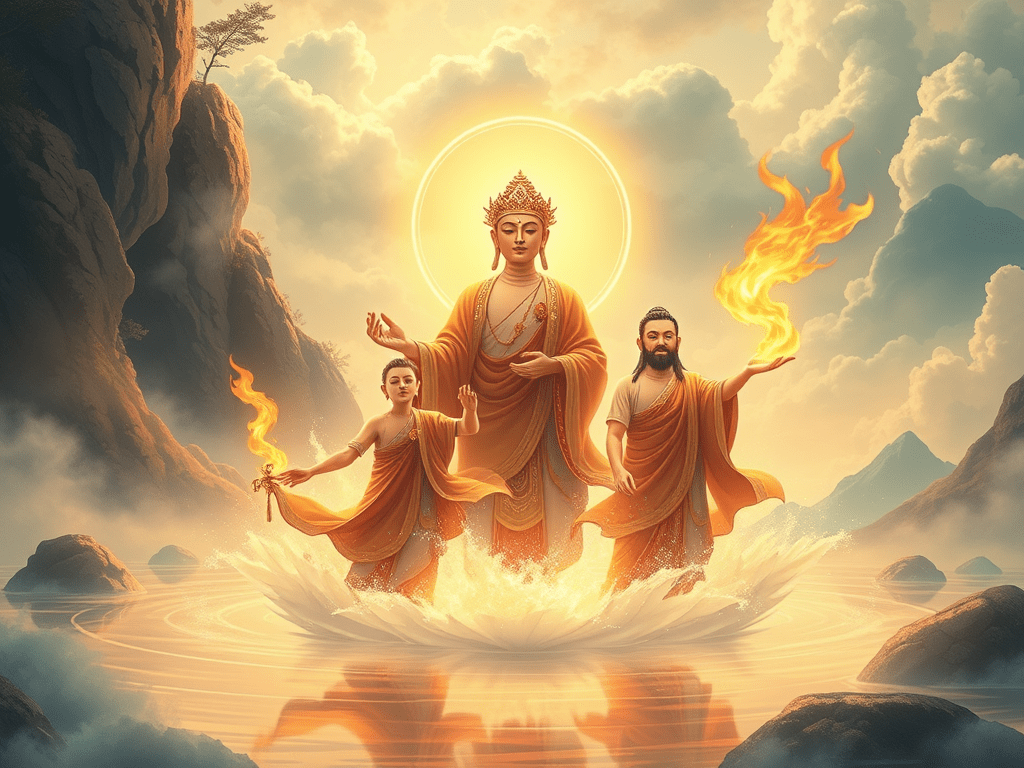

Chapter Twenty-Seven of the Lotus Sūtra presents a narrative where two sons, Pure Storehouse and Pure Eye, perform extraordinary “wonders” – such as walking on water and emitting fire – to convert their father, King Wonderful-Adornment, to Buddhism. While these feats are described as literally transcendent, this report argues they are not to be taken at face value as a goal for practice. Instead, they function as “a profound allegory for the transformative power of the bodhisattva way.” The true “wonders” are the “deeply personal and social changes that manifest from diligent practice—the capacity to develop unwavering respect for all beings, to control destructive desires, to remain undaunted by life’s tragedies, and to inspire the spiritual awakening of others.” This interpretation bridges the gap between ancient miraculous narratives and contemporary Buddhist emphasis on internal transformation, ethical conduct, and social engagement.

II. The Narrative of Transformation: King Wonderful-Adornment’s Awakening

The chapter recounts a past life story where King Wonderful-Adornment, a staunch follower of Brahmanism, is challenged by his wife, Pure Virtue, and their two sons, Pure Storehouse and Pure Eye, who have already cultivated the bodhisattva path. The sons, possessing “mighty spiritual powers, blessings, virtues, and wisdom,” are instructed by their mother to “manifest spiritual transformations” for their father. This is a deliberate and compassionate strategy, not an act of self-glorification, aimed at “purify[ing] their father’s mind, belief, and understanding.”

The sons’ “wonders” include:

- Walking, standing, sitting, and reclining in midair.

- Emitting fire from their lower bodies while water streamed from their upper, and vice-versa.

- Manifesting in huge bodies and then becoming small.

- Entering the earth as if it were water and walking on water as if it were earth.

These displays lead to an immediate and profound effect on the king, who “rejoiced greatly and gained what he had never experienced before.” His mind is purified, leading him to ask, “Who is your Master? Whose disciples are you?” This pivotal question signifies his openness to a new path. The sons’ actions are rooted in compassion, performed “Out of concern for your father,” underscoring that these powers are a “skillful means” (upāya) for spiritual liberation. The narrative highlights that the ultimate “wonder” is “the compassionate motivation that gives it meaning and purpose.”

III. Philosophical Context: Abhijñā, Upāya, and the Buddha’s Ambivalence

The supernatural powers described are known as abhijñā (“extraordinary knowledge and powers”), with physical feats termed ṛddhi. While the first five abhijñā are common across various Indian ascetic traditions, the sixth and most crucial is “freedom by undefiled wisdom,” unique to the Buddhist path.

The Buddha, particularly in the Theravada tradition, often cautioned against the indulgence in these powers, viewing them as a “powerful distraction from the path toward enlightenment.” This apparent contradiction in the Lotus Sūtra is resolved by understanding the “wonders” as a skillful means (upāya). The sons use these powers not for personal gain but as a selfless, compassionate act to break through their father’s “specific delusion.” The value lies “not in the possession of the power, but in the compassionate intention with which it is used.”

The six abhijñā can be reinterpreted metaphorically for modern practice:

| Traditional Interpretation | Modern, Metaphorical Interpretation |

| Divine Eye | Deep insight into the true nature of reality, perceiving interconnectedness and inherent potential. |

| Divine Ear | Genuine hearing and comprehension of others’ suffering, transcending superficial words, cultivating profound empathy. |

| Knowledge of Others’ Minds | Unprecedented compassion and intuitive understanding of others, allowing for skillful guidance and support. |

| Recollection of Past Lives | Profound grasp of the principle of causality (karma), understanding how past actions influence the present. |

| Supernatural Powers (Ṛddhi) | Unshakable resilience and conviction in one’s practice, empowering one to navigate any challenge without being overwhelmed. |

| Freedom by Undefiled Wisdom | Attainment of enlightenment (bodhi) and a life state characterized by absolute freedom, wisdom, and compassion. |

The true “wonders” for modern practitioners are manifestations of inner transformation and ethical conduct:

- The Wonder of Purifying One’s Mind: This aligns with the king’s experience of overcoming “fundamental ignorance” and “self-belittling attitudes” to conceive a desire for enlightenment. The sons’ ability to “walk on the water as if it were earth, [and] entered the earth as if it were water” metaphorically represents a mind “so strong and centered that it can navigate the turbulent ‘waters’ of life’s challenges without being swayed or overcome.” This is the capacity to “control our desires and not be devastated by life’s tragedies.”

- The Wonder of Respect: This involves “not a passive tolerance but an active engagement that recognizes the inherent dignity and potential—or Buddha nature—in every person.” Sharing the Dharma, as the sons do, is rooted in profound respect. This aligns with the Mahayana concept of the non-duality of the person and the environment (Eshō Funi), where an individual’s transformed mind directly impacts their surroundings, shifting perception from suffering to a “buddha realm.”

V. The Wonder of Shared Practice: Nichiren’s Teaching

Nichiren’s teaching democratizes the concept of “wonders.” He emphasizes the power of “sharing even a word or phrase” of the teaching, referencing the Lotus Sūtra’s “Teachers of the Law” chapter, which states that anyone who “secretly preaches the entire Lotus Sutra or a phrase of it to even one other person, then you should know that this individual, indeed, is an envoy of the Tathagata.” This simple act is considered a profound wonder because “the ‘word or phrase’ contains the entire ‘great dharma enabling all the people to attain Buddhahood.’” It is an act of compassionate propagation, inspiring others to awaken to their “unlimited potential and power.”

VI. The Bodhisattva Path: Social Engagement and Collective Liberation

The narrative of King Wonderful-Adornment’s family provides a model for the bodhisattva path, which begins with intimate relationships—”the parents and immediate family members are the first objects of our practice.” This personal transformation creates a “positive ripple effect” for broader societal change.

- From Individual Happiness to Social Peace: Nichiren Buddhism, particularly “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land,” emphasizes the “inseparability of individual happiness and societal peace.” The king’s transformation prepares him and his household to contribute to society’s peace and security.

- The Modern Bodhisattva and Engaged Buddhism: Contemporary Engaged Buddhism expresses these principles by applying Buddhist ethics to systemic and structural problems like poverty, racism, and environmental degradation. The king’s question, “Who is your Master?”, highlights that the goal of the “wonders” is not to impress but to inspire genuine interest. The ultimate fulfillment is when a practitioner’s life is so characterized by “compassion, resilience, and happiness that it inspires others to ask, ‘What is it about you that makes you this way?’”

Summary of Personal vs. Social ‘Wonders’:

| Personal Transformation of the Practitioner | Social and Environmental Impact |

| Cultivating an indestructible life state of happiness and resilience. | Contributing to the peace, security, and prosperity of society. |

| Overcoming “fundamental ignorance” and “self-belittling attitudes.” | Inspiring others to awaken to their “unlimited potential and power.” |

| Controlling one’s desires and not being devastated by life’s tragedies. | Guiding others to overcome their own sufferings through compassionate action. |

| The ability to see and respect the inherent Buddha nature in all beings. | Fostering a culture of peace, non-violence, and shared dignity. |

| The transformation of a personal life state through consistent practice. | The realization of a “buddha land” in the immediate environment. |

The “literal wonders” of the Lotus Sūtra are a “powerful and skillful means to convey a deeper and more profound truth.” The story of King Wonderful-Adornment and his sons remains a timeless model for the bodhisattva path. The true “wonders” are the “transformative power of a life changed by Buddhist practice—a life characterized by unshakable resilience, deep compassion, and an unwavering commitment to the happiness of others.” This ancient narrative, through allegorical interpretation and teachings like Nichiren’s, remains profoundly relevant, guiding practitioners to become “Good and Wise Advisor[s]” who use their personal transformation as a “light to ‘purify the minds of others.’”

Leave a comment